Franchising’s fast track to freedom

Restless employees have long dreamed the dream of being their own boss. But in the 1990s, the old entrepreneurial impulse has taken on new urgency. With the remolding of corporate America, many of us won't stay at one company long enough for the gold watch and the misty good-byes

You may, in fact, be asked to leave before you want to go, and chances are no one will be eager to give you a new job.

Whether they've been fired or just plateaued, thousands of ex-execs are finding the solution to their career problems in a franchise. A recent survey of 229 franchise companies, conducted by DePaul University and Francorp, a franchise consulting firm in Olympia Fields, Ill., revealed that 35% of the franchisors polled had franchisees who had held jobs as corporate managers. Further-more, predicts William Cherkasky, president of the International Franchise Association, "as industry makes cutbacks during the recession, more executives are going to have to buy themselves a job. They'll take out second mortgages and use their lump-sum severance packages to finance franchises."

Former corporate managers already own enterprises ranging from hair salons to fast-food restaurants to regional business publications. Franchisees usually start at the bottom, learning the business from burger flipping on up. But they quickly graduate to their true role: managing a business. This means everything from reviewing daily sales receipts to motivating employees. And many franchisees gravitate to enterprises tied to their special talents or interests.

Franchising is a low-risk route to business ownership; fewer than 4% of outlets close down each year. If, however, you're one of the unlucky 4%, you're likely to lose not just your business but your house and retirement money too.

The key to franchising success is having a product or service that is in high demand and a franchisor who will be with you every step of the way. Of course you pay for all this. The franchise fee alone-your price of admission-can run as high as $22,500 for a well-managed operation like McDonald's.

The average total initial investment is $137,000, of which $19,000 is the franchise fee. The rest may include such items as insurance, equipment and inventory. Figure on paying royalties of 2% to 6% of gross sales. With all these costs, you'll have to be patient about getting a return on your investment: it can take three to five years.

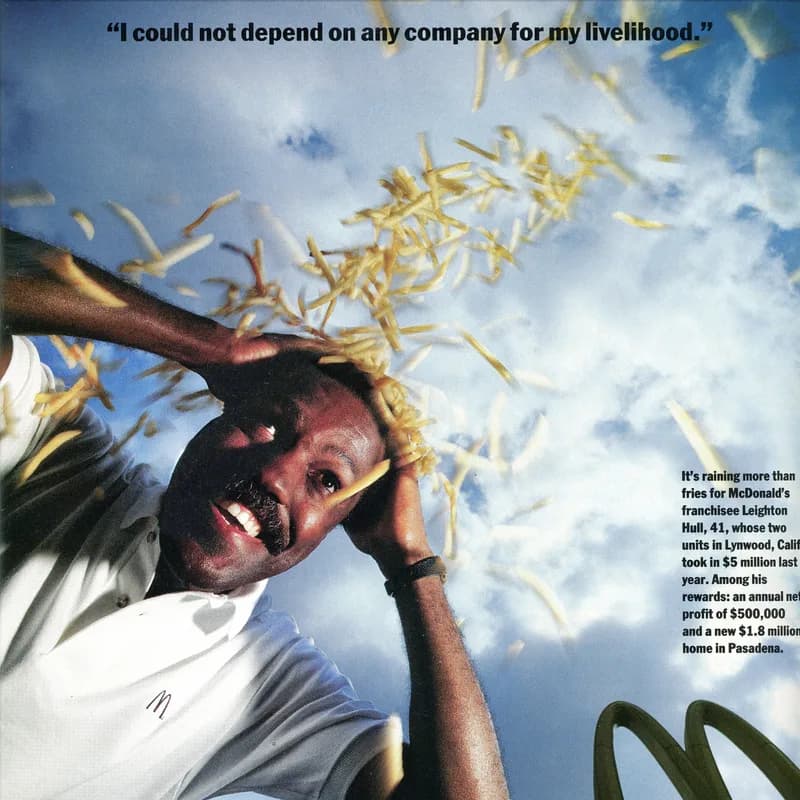

Leighton Hull's very golden arches

Some McDonald's franchisees have to wait a year for units.

The most selective school in America isn't Harvard, Stanford or Annapolis. It's Hamburger University in Oak Brook, IIl., where new McDonald's franchisees earn their fast-food baccalaureates. Of the 2,000 or so who apply each year, barely 200 are admitted. But while those who pass through Hamburger U.'s portals may remain deficient in quantum mechanics and may never deconstruct a paragraph of Proust, they'll probably be rich-like Leighton Hull, 41, who takes home about $300,000 a year from his two McDonald's units in Lynwood, Calif.

In 1975, after two years as a marketing representative at Cummins Engine Co. in Columbus, Ind., Hull was one of 1,700 Cummins employees laid of.

That day, he says, "I decided that I could not depend on any company ultimately for my livelihood." Nonetheless, he held a series of government and corporate jobs, first in Indianapolis and later in Los Angeles, helping launch a series of small businesses before making his own move in 1983.

After lengthy interviews with a McDonald's licensing manager, Hull was accepted as a franchise trainee. For an up-front fee of $4,000, he got to work 50 to 60 hours a week for five months without pay at a local McDonald's, doing everything from fixing milk-shake machines to mopping floors. In addition, he spent two weeks taking management courses at Hamburger U. Unencumbered by a full-time job, Hull finished the training program —normally a two-year process-within six months. He and his wife Brenda, now 38, subsisted on their savings and the $35,000-a-year salary she earned as an accounting manager with the Atlantic Richfield Co.

Four months into his training, Hull received exceptionally good news: not only was he accepted as a franchisee—a decision McDonald's reserves until it deems a candidate fit-but he would have the only unit in Lynwood, Calif., near his home. Some new franchisees have to wait a year to get their units, and some have to relocate.

To get started, Hull had to put up $66,000 in cash, which is only about a quarter of the usual cash investment.

This boon came through McDonald's Business Facilities Lease Program, which allows beginners with limited means to lease signs, equipment and furnishings so that they can save enough capital to purchase the franchise. (Mc-Donald's owns the real estate.) Hull was able to buy his unit in a little over a year, all the while paying himself an annual salary of about $48,000. The total price for his franchise, including close to $300,000 in renovations: $1 million.

Four years later in 1988, he bought his second unit for $700,000, financing it with a secured bank loan, using his first franchise as collateral plus funds generated by the outlet. The two outlets grossed $5 million in 1989. (Average annual sales for a McDonald's franchise:

$1.6 million.) Net profit, or income, was $500,000, with $300,000 going to Hull's salary and the rest largely toward the acquisition of new outlets. (Hull's company, like many other franchises, is a sole proprietorship, in which the corporate profit is also the proprietor's in-come.) In three years, he has seen a spectacular 80% return on a total investment of $300,000 in personal funds.Current market value of the restaurants: $2.8 million, up 65% since he bought in.

Hull works hard for his half a million. He puts in 60-hour, six-day weeks, supervising 175 employees. When he started out six years ago, he worked as many as 100 hours a week, often bedding down in his basement office.

The fruits of all his labors are abundant, however. Brenda was able to quit her job at Arco after their daughter Sydney was born four years ago. The family is currently trading way up from their $299,000 condominium to a 6,000-square-foot, $1.8 million Mediterranean-style spread. Hull has even managed to gain more time with his family. "I can choose not to come to work on Monday or Tuesday and take my daughter to the zoo," he says. "I don't work any less hard, but now I have options."

Take a long look before you sign up

Talk to a few franchisees who have been in the system for at least five years.

Getting into franchising may well be the single biggest financial step of your life. The initial investment alone can wipe you out if your franchise does not succeed. So before you even think of signing any agreement:

- Get your family on board. Running a franchise is far from a nine-to-five proposition, a fact that can be corrosive if it comes as a surprise to your spouse and children. Besides, family involvement can reduce personnel costs and give your kids a chance to learn the business.

- Make sure the industry appeals to you. You'll be signing a contract for as long as 20 years. To find a field that fits your experience and interests, shop the International Franchise Association expositions held about 12 times a year around the country. Unlike some other franchise show operators, IFA carefully screens exhibitors. For details on locations and dates, call the Blenheim Group, a trade show company that manages the IFA expos, at 407-647-8521.

- As you find franchises that interest you, ask for a copy of each company's disclosure statement, which provides financial and other key information about the franchisor, or the more comprehensive Uniform Franchise Offering Circular (UFOC), a 23-item prospectus that includes all the legal and financial information you'll need for a preliminary sizing up. Consider hiring an accountant to review the franchisor's financial statements.

- Watch out for scams. A tip-off: when you're asked for an up-front fee without getting a disclosure statement or the UFOC. A federal regulation stipulates that prospects cannot pay any fees until 10 days after reviewing the disclosure statement or UFOC. The FTC requires franchisors to provide a list of all franchisees in the applicant's state in the disclosure statement. It there are fewer than 10, names of franchisees in nearby states must be substituted. In such cases, be wary of the out-of-state contacts you may receive. Many fraudulent operators employ "singers," individuals posing as successful franchisees who will endorse the disreputable franchisor over the phone. Check with the Better Business Bureau if you are unsure of a franchisor's honesty. Some frauds place ads in local papers and set up phony offices.

- Personally inspect half a dozen or so franchises. Try to visit franchisees who have been in the system a year or so to gain a firsthand feel for the company's recent training practices. Talk to a few franchisees who have been in the system for more than five years. You should consult all franchisees you interview about sales performance, profitability and return on their cash in-vestment. Franchisors will not disclose earnings, however, unless they are in the UFOC. Reason: it's against the law.

- Once you have zeroed in on a franchise, have an attorney well versed in franchise law review the agreement. For help in evaluating the entire deal, send $9 to International Franchise Association Publications, P.O. Box 1060, Evans City, Pa. 16033 for the handbook Investigate Before Investing.

LEIGHTON HULL