FOR YOURSELF, BUT NOT BY YOURSELF

Leighton Hull, of Oxnard, California, came into our system in 1995; in that time, he has developed several Denny's franchises in California and is looking to expand. Leighton is not the kind of man who would be bothered with Denny's if he didn't think we were serious. "I've been a hard-core, card-carrying activist for many years," he said. "Denny's has made good on what they said they were going to do. The name of the game now is the board room, and if you don't change, you can't take advantages of the opportunities."

When It All Works, It Works Really Well

Leighton's activist credentials within the black community are notable. Not only has he been acquainted with some of the top leaders of the NAACP over the years, but he also was the economic coordinator for the Million Man March in Washington, D.C. in 1995. Leighton was an unhappy ex-franchise holder at McDonald's when he ended up applying to Denny's. Before that, he was a graduate of Indiana University who had also attended the entrepreneurial programs at Wharton and Harvard. He also worked for awhile as a marketing representative at Cummins Engine and at the Indiana Department of Commerce, helping minority businesses with technical assistance under a program sponsored by the federal government. Some of these things may not be what you'd expect a Harvard man to do, but Leighton, a native of South Bend, Indiana, knew what he wanted. "After leaving school, I decided to go back and give something to the community." It is not unusual for African-Americans who have been fortunate in receiving a top-notch education to feel that they should use their skills and talents to benefit other black Americans who could use their help.

Leighton relocated to California in 1980 and did the same sort of business as a private consultant. That's when he got the franchise bug. He helped a client with an application to be a franchisee at Goodyear, the tire company. He spent weeks helping the client get the paperwork in order so that the bank would give the man the loan he needed to start the business. The bank approved the loan, and Goodyear was ecstatic at having gotten such an expertly prepared package. The company asked their new franchisee who had helped prepare his application. "Leighton Hull," the man said

Goodyear got in touch and told Leighton how impressed they were with the documentation his client had presented. Would he be interested in running a Goodyear franchise himself, they wanted to know. Goodyear was so eager for Leighton to join them that they not only started looking for a site for his franchise but also pressed him to find other applicants. Leighton was ready to give it a try, and not just because he was an entrepreneur. It was 1984 and "My wife was going to have a child," Leighton said. "I needed a business that could go on without my actual presence all the time."

Now 1 would love to tell you that Leighton immediately picked up a phone and called Denny's-but that's not quite what happened. He decided to take a chance with what many outside the restaurant business consider the surest and safest of franchises: McDonald's. Said Leighton, "I had heard that McDonald's had tons of applications and it took years for them to approve you. I just put in there because I thought I had nothing to lose. I later heard that there were more than twenty-five thousand applications in 1984 and McDonald's acted on [only] two hundred twenty-five."

Leighton Hull's application was one of the 225. All McDonald's operators are expected to go to their headquarters for a period of training, and Leighton dutifully did his tenure at Hamburger University in suburban Chicago while his store was being constructed and his pregnant wife waited back home in metropolitan Los Angeles. He came back and his very own McDonald's was completed and opened in March 1985. In November of that year, his wife gave birth.

Leighton went on to build and open a second McDonald's franchise in southern California in 1989. As it is with most franchisees, it seemed easier the second time around. But it wasn't to stay that way. In the early 1990s, McDonald's, said Leighton, began to ratchet up the number of restaurants in the system. He says that some of those new restaurants opened up uncomfortably close to his franchises and ended up siphoning off customers that otherwise would have been his.

There was real friction between Leighton and McDonald's over this, and he ended up selling the two franchises back to McDonald's in 1995. Even before that hap-pened, however, Leighton had taken a trip to Las Vegas, where he met up with an old friend-Fred Rasheed of the NAACP, who was negotiating the fair share agreement between the NAACP and Denny's. Rasheed said he was in Vegas for a business conference, and called Leighton, whose home was then in Pasadena. Over lunch in a casino hotel restaurant in Las Vegas, Rasheed broached the idea of a Denny's franchise to Leighton.

"He knew that they were interested in finding some minorities and African-Americans," said Leighton. "He also felt that Denny's was on the launch pad for growth and development as well as having signed on to the fair share projects. I told Fred 1 was interested in unlimited growth opportunities and I didn't care from whom."

To this day, Leighton maintains that the incidents that once plagued Denny's were the result not of systematic and planned discrimination but of the quality of some of the restaurants. "It does not," he said, "mean that you should condemn sixteen hundred other stores. At the time, I had heard about it, but I really didn't know a whole lot about what was going on. I figured nobody could be that stupid." Leighton, as you can see, speaks his mind.

So he called up one of Denny's franchise representatives after meeting with Rasheed and had a frank discussion of the whole slew of incidents that had marred our reputation.

Afterward, he was willing to enter into the process of becoming a franchisee with Denny's.

It takes roughly 90 days for an application to be approved. That's the time it takes for us to go over the paperwork and do our due diligence, for the applicant to come up with financing, and for us to make sure we have the right person. It takes roughly 9 months to 1 year after that for the restaurant to be constructed and the doors to open for business.

But within that time, we conduct a series of interviews to check on an applicant's integrity, reliability, and character-the things that count beyond financial assets. Every prospective franchisee has to come to Spartanburg and sit down for an interview with three people from headquarters.

One is Jim Lyons, and the two others can vary-they can be from various divisions within the company, but one must always be a person of color. We want to show these potential franchisees that we are serious about diversity at the top levels, and we want to judge their seriousness about our goals at the same time.

This last phase of meeting with people from headquarters was not in place when I got here, though I did meet Leighton back in 1995, shortly after I arrived. The interview system, not fully operational until early 1998, was one of the innovations we have implemented over the past few years that is designed to strengthen our selection of franchisees. Those meetings, along with all the other actions I've described, have helped boost our numbers.

Leighton, to this day, is cordial and enthusiastic about Denny's. Fred Rasheed, however, remembers nothing but footdragging surrounding Leighton's application to be a franchisee. Though Fred put in more than a good word, he thinks that some of the people in the system just took their sweet time about getting Leighton his approvals.

Could be. But I know that that sort of thing could not happen now.

Leighton has come into our system with extraordinary energy. In 1995, he bought three of our company stores in Ventura County, California, and purchased three more Denny's stores in northern California in 1998. He built a new one last year in Ventura, California. All told, he now has seven franchises in the state and is currently working on acquiring more restaurants, including a new restaurant in Watts. With the funds from the sale of his McDonald's franchises, along with his prior experience of running a fran-chise, Leighton certainly was ready to join the Denny's family.

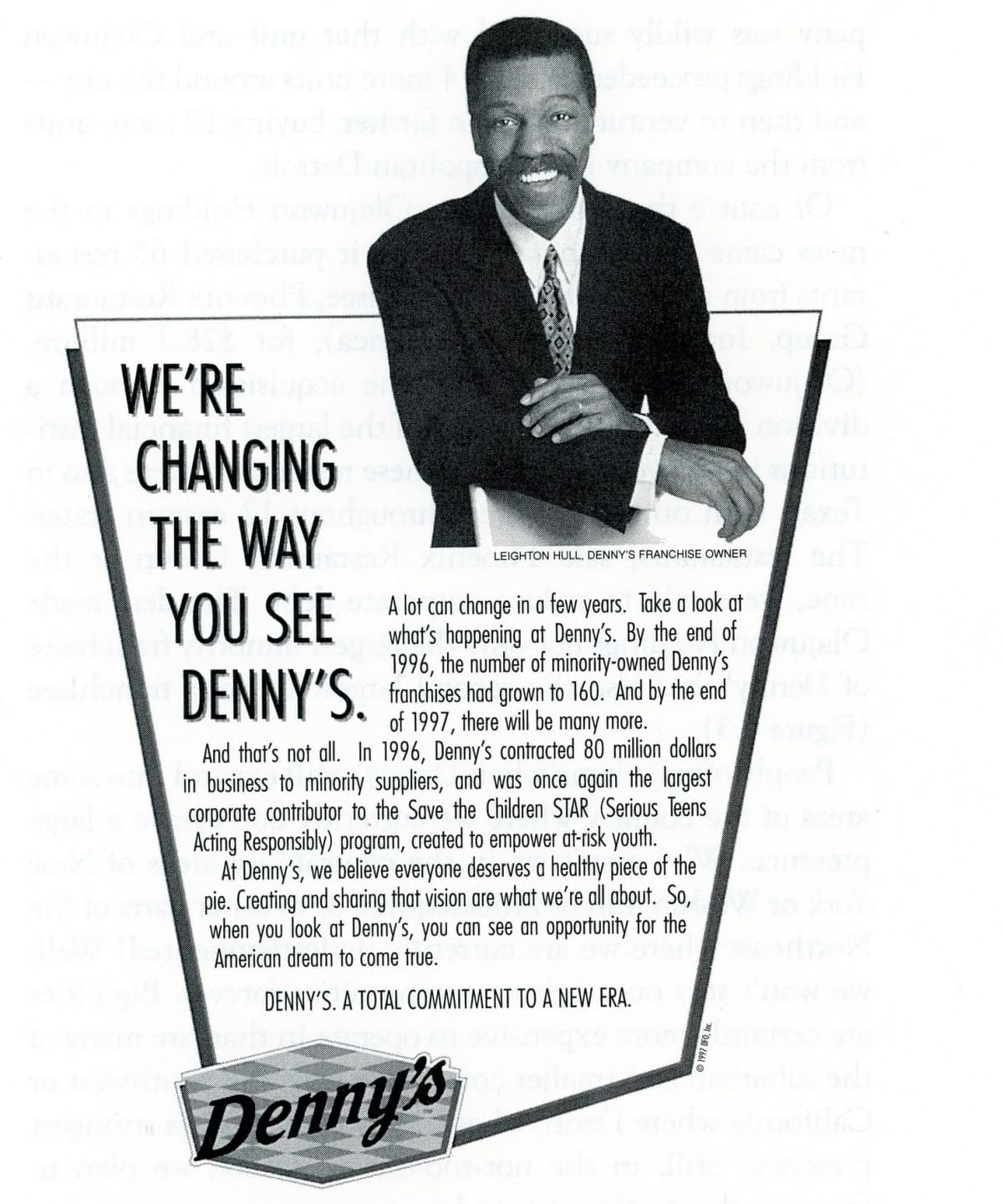

WE'RE CHANGING THE WAY YOU SEE DENNY'S.

Leighton Hull is one of Denny's over 100 minority franchise owners. A Denny's franchisee since 1995, Hull now owns seven Denny's in California and is looking to expand. He was featured in a Denny's print advertisement that appeared in Black Enterprise Magazine, Jet, and Ebony.

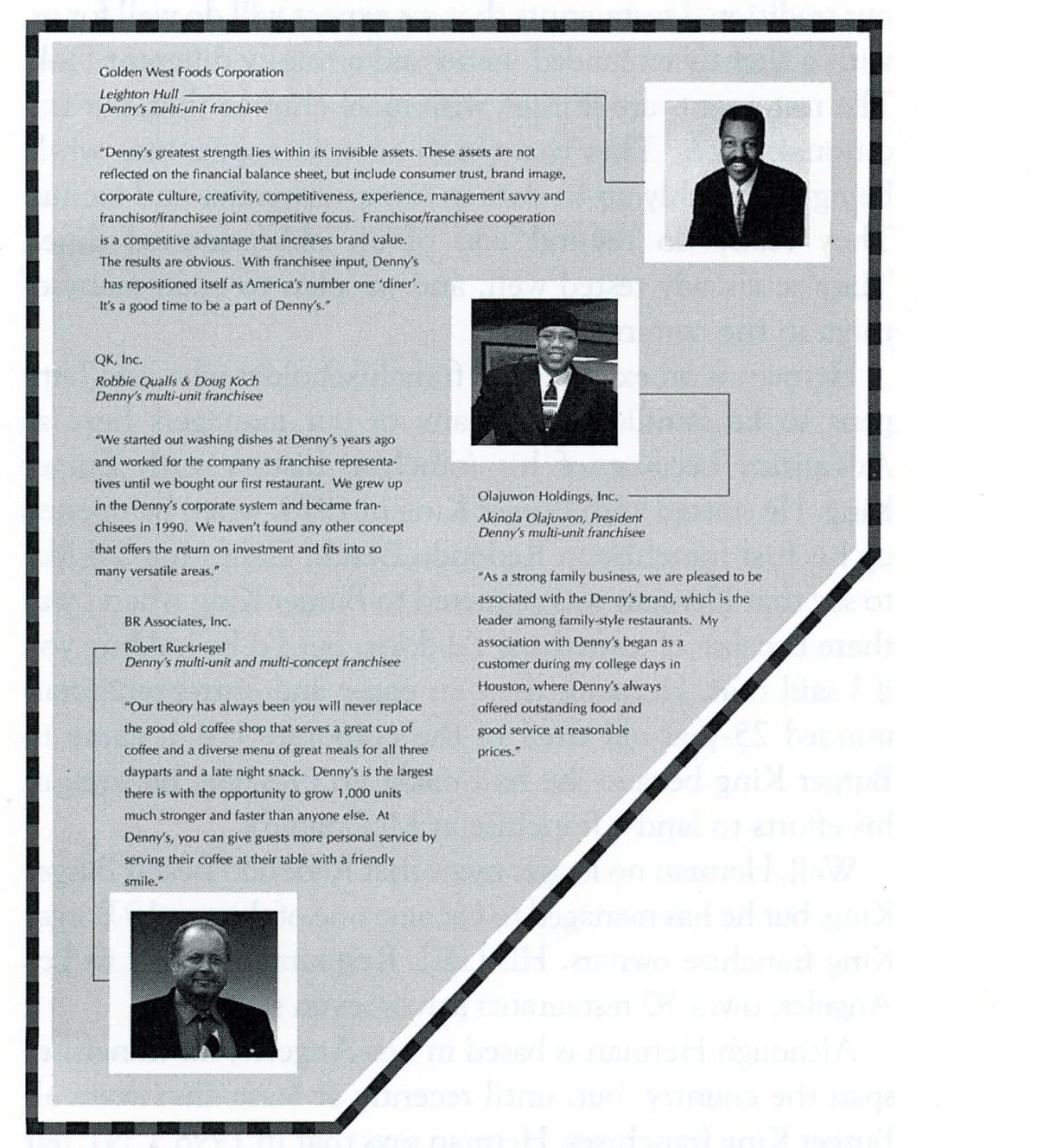

Denny's franchising packet features statements from several multi-unit franchise owners including Akin Olajuwon of Olajuwon Holdings, Inc., the second largest franchisee in the Denny's system, which owns over 75 restaurants in several states. This is a page from the franchising packet, which is distributed to prospective franchisees.

LEIGHTON HULL